No end in sight for 9/11 suspects’ trial

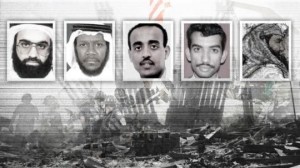

Fourteen years since the Sept. 11 attacks transformed the nation and launched two wars, the five men accused of masterminding the crime are still waiting for their trial to begin in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his four associates have been in U.S. custody for more than 10 years. But the latest in the military’s hapless effort to try them — which began in 2012 — has ground to a halt, as the judge, Col. James Pohl, addresses allegations that an FBI informant attempted to infiltrate one of the defendants’ legal teams. The court hasn’t been in session since last April when Pohl declared the proceedings suspended again after 30 minutes. Even if he solves this particular problem when the court reconvenes next month, dozens of other motions and complaints that have been on hold for a year and a half await him.

The handful of people who have been watching the excruciatingly slow case closely — journalists, family members of those killed on Sept. 11, attorneys — say they believe it will be years before a jury is selected and the trial actually begins. Some have given up hope that the five accused mass murderers will ever face justice.

The handful of people who have been watching the excruciatingly slow case closely — journalists, family members of those killed on Sept. 11, attorneys — say they believe it will be years before a jury is selected and the trial actually begins. Some have given up hope that the five accused mass murderers will ever face justice.

“I don’t know if it’s going to happen in my lifetime,” said Rita Lasar, 83, whose brother died in the 9/11 attacks. Lasar formed an organization called Sept. 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, which lobbied unsuccessfully for the accused plotters to be tried in the federal court system.

The Obama administration attempted to move the five men from Guantánamo to be tried in a federal court in Manhattan in 2009, before fierce political blowback led by a vocal faction of 9/11 families killed the plan. (The Bush administration began trying the five in a military tribunal, an approach that was slapped down by the Supreme Court.) Congress passed a law blocking all transfers of Guantánamo detainees to U.S. soil. Obama reformed the military commissions, to be more palatable to human rights critics, and restarted the proceedings there in May 2012.

Rita Lasar

Those opposed to the move to federal court wanted swift military-style justice for the accused plotters in a tribunal that made it easier to get convictions and guard government secrets. But the result has been very different. The untested system is a “defense lawyer’s absolute dream,” according to David Remes, who represents several Guantánamo detainees. Attorneys are able to file motion after motion, delaying the start of the death penalty trial, in part because no one really knows what the rules are. In the meantime, the federal court system has successfully convicted terrorist after terrorist.

“There’s no question that if these cases were tried in federal court, they would have been over long, long ago,” Remes said.

But Jason Wright, a former attorney on Mohammed’s defense team before resigning last year, said that the ever-changing rules of the new court were not a bonus for him or his team.

“I think the biggest challenge is trying to litigate in an environment where the rules change constantly, where Kafka controls the design,” he said. “You’re told to follow rules that you’ve never been shown, especially the classification rules, and it’s just extraordinarily difficult.”